By Julie Wakeman-Linn

In 2020, when they announced a horrendous pandemic, I contemplated who I would lose to it—aging relatives or friends one and two decades older than me. It was not who I expected. No—it was one of my dearest friends. My partner in writing who respected the words above all else but who also loved me through the hard times of a child’s injury, the shocking surprise deaths of each of our sisters , through all kinds of trouble. We practically shouted encouragement at each other that we must not give up, we must keep writing or “the bad guys win.”

That March, she shrugged it off. “It’s only a virus. We wash our hands. It’s nothing.” Except it got her—bad. No hospitalization, no ventilator, but three long weeks of misery. We reconnected, trying to find our rhythm on Zoom or lunch outside. It didn’t work. She hated Zoom.

In May she announced her husband had bitterly complained about her vinaigrette. Un-eatable. Too much vinegar? Too much balsamic? She didn’t clarify. She’d lost her sense of taste and of smell.

Through the interminable summer, I struggled against the excruciating political climate, marched for racial justice, and I often sought out my granddaughters, withdrawing into a safer, cuddly bubble. One set of friends met weekly in their back yard to laugh, drink, eat good take-out, and fantasize where we would travel on our first post pandemic trip. I called them my sanity circle.

Week in and week out, my writing partner would flit into contact and then disappear again sometimes for a month. Finally in January 2021, on a balmy day, ten months after she’d been sick, we met to walk and talk.

“Turn your head and hold your breath.” She swooped me up in a huge hug. I smiled, all the way down to my cellular level.

We walked for an hour and a half. I heard the details of drinking milk that had gone bad, starting a fire on the stovetop from not being able to smell the smoke, of eating way too much high-fat content for the “mouth feel.” Alcohol relaxed her but she wasn’t enjoying that either, unable to distinguish a vintage Cab from grocery store plonk. I listened and tried to comprehend.

For over ten years, we had met weekly to share pages, brainstorm projects, and shake off life’s vicissitudes. I should be able to understand, but I really couldn’t.

Throughout our long friendship of lunches, on rough weeks when life ran over us as mothers, daughters, wives, we’d have cheeseburgers. The Irish cheddar a velvet blanket over the beef. I‘d order fries and she would steal a single salty, crispy, golden fry. On good weeks, with an acceptance or a proposal, we’d splurge on fish tacos with the pico de gallo tart, pungent, with just the right size of onion bits. As we discussed, particularly my rough drafts, she’d push for me to sit in the moment to feel the image, of course summoning as many sensory details as I could. She says now she can’t, but I wonder if she is capable of remembering, if tapping into sense memory would help her evoke the sensations.

On our January walk, she, one of the liveliest people I have ever known, declared she was “dull.”

“You are not,” I stridently corrected her, but she wasn’t hearing or believing me.

After that walk, she faded away from me. I raged—what had I done for her to dump me? I nudged her back, “we must write our Monday 1000.” She complied once. It was terrific. She read a revision of mine and eviscerated it. As she talked that day, our first writers’ lunch in months, her comments and feedback, which began positively, spun darker and nastier. Our contract broken, her anger and depression bleached the conversation of its honesty. How do I know? In that conversation, she began to contradict her own feedback.

I came away, not injured, but considering her behavior. It wasn’t me after all. Nothing I had done or said or complained about.

Late in April 2021 when the COVID vaccine lifted other acquaintances’ brain fog, migraines and loss of senses, I prayed full vaccination would work for her. It didn’t.

Two months have gone by after my last friendly, “come back to the writing life” message. She ignored it. Depressed people sometimes need to be reached out to anyway I reasoned, so I sent a friendly, no-obligation email, and she came back with a relative non sequitur about Sylvia Plath’s publication history. I gently reminded her “we must not give up,” to which there has been no reply.

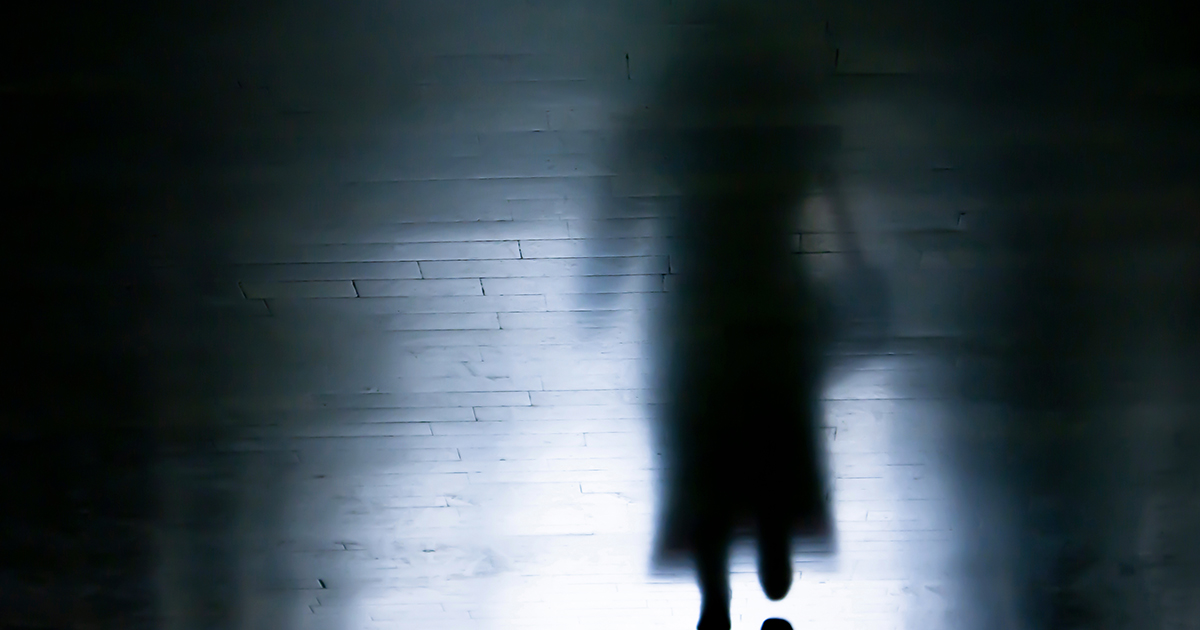

On the surface, she is lost to me but, on the inside, I fear she is truly lost in herself.