By Tiffany Amoakohene

How do you grieve for someone you love, but don’t like? I must’ve asked myself this question a thousand times when my mother died. I kept those complicated emotions to myself like a dirty little secret.

My mother is dead. The words didn’t make sense. Even though she’d been afflicted with various ailments over the years, I thought my temperamental, strong-willed mother was indestructible. I thought she would outlive me. I thought she would outlive all of us.

It had been two hours since I received the news, two hours since I’d cried in my co-worker’s car as she drove me home. Now, I was home alone with my grief. So many questions flooded me all at once. Was she scared, did it hurt, did she know it was coming, did she die of a broken heart instead of cardiac arrest?

I was still in shock. One minute I was crying and screaming as if I’d lost a limb and other times I felt completely disconnected and numb. My emotions were raw and conflicted, caught between loving the woman who had given me life and resenting the mother who was the source of some of my greatest anxieties and fears.

The sound of the doorbell startled me. When I raised the broken blinds, I saw a stocky middle-aged man wearing a matching Red Sox hat and jersey holding a toolbox adorned with baseball decals.

“Can I help you?” I shouted from the window.

“I’m here to fix the broken doorknob,” he said in a thick Boston accent that sounded more like a question than a statement.

He did most of the talking, and I did most of the listening while he focused on removing the outer handle from the balcony door. I usually hated small talk, but the Red Sox-loving handyman surprisingly became a welcome distraction.

“My mother died,” I blurted out breaking the spell of normalcy.

The more I said it out loud, the more it became real, but when I watched his animated expression disappear, I instantly regretted roping him into my emotional train wreck.

“Sorry, I didn’t mean to spring that on you,” I said.

“Don’t apologize,” he said. “I’m so sorry for your loss.”

I expected him to keep fixing the doorknob, but he put down his Phillips Head screwdriver and talked about the pain of losing his own mother.

“I was just glad she made it to the ninth inning,” he said. “The ninth inning is what I call the last stage of life. I love a good baseball metaphor. She was eighty-three years old. She lived long and she lived well.”

I realized that my mother hadn’t made it to the ninth inning. She was only fifty-eight.

As he continued repairing the doorknob, he talked about the different stages of grief, originally meant for the dying, but applied to the mourner—denial, anger, guilt, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.

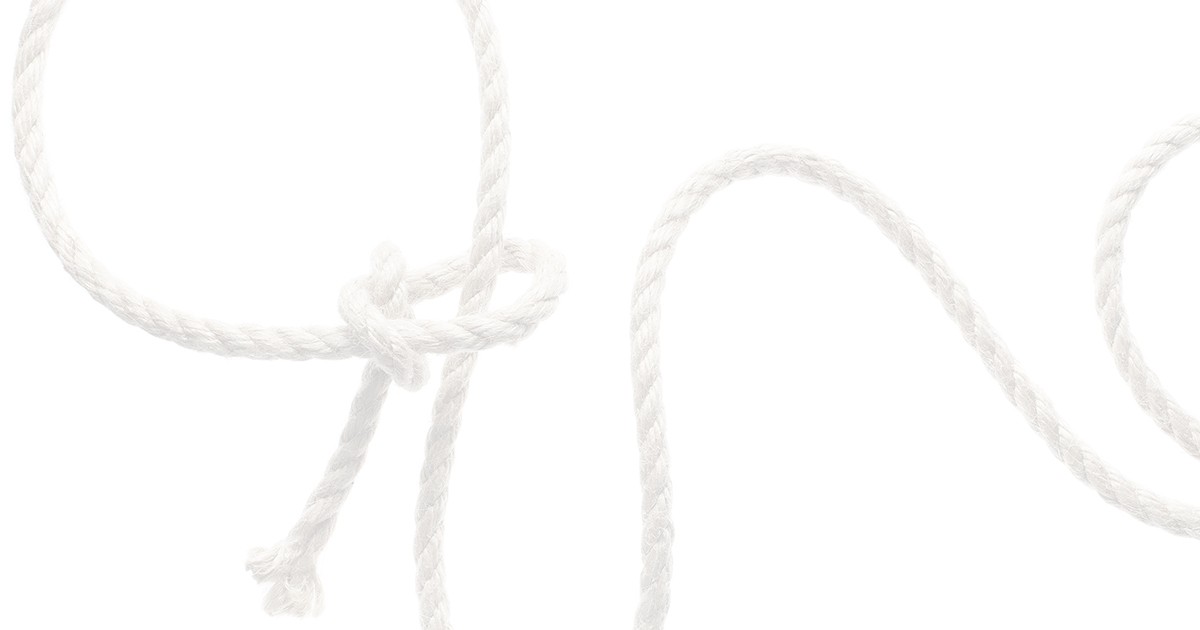

It wasn’t until several months later that I realized he’d left something out. He’d forgotten to mention the unanticipated sense of relief; the healing moment of liberation that occurs when you feel yourself being released from an endless chokehold. I couldn’t fault him for his unintentional oversight. After all, he had no way of knowing that he’d been consoling the daughter of a bipolar mother. He had no idea that I’d been wearing an invisible lasso around my neck my entire life. It would be months before I leaned into that sense of freedom.

***

When I sat next to my brother in the funeral parlor, I couldn’t take my eyes off the two miniature busts that sat on opposite ends of the mahogany mantel. I watched their bronze reflections extend into infinity in front of a rectangular mirror as I listened to burial options. My brother was focused on the price tag.

I turned my attention back to the wonky-eyed funeral director and his large veiny knuckles that looked like they were about to pop out of his fingers. As soon as my brother heard how much it would cost to bury our mother even without all of the bells and whistles, he elected cremation.

“Ten thousand dollars is a lot of money,” said Phil. “I don’t know about you, but I don’t have that kind of money stashed away.”

Our mother had never made anything easy for us, and it was no surprise that she hadn’t left behind a single clue about what she wanted postmortem. But one thing I knew for sure was that cremation wasn’t it.

“I want to rise from the dead fully intact,” she’d once told me. “You can’t get into heaven when you’re falling apart.”

“I’ll give you two some time to sort things out,” said the funeral director.

After he hobbled out of the room, I noticed several missed calls on my cell phone, including one from my recruiter, Jinny. I knew it wasn’t the right time to tell my brother about my plans to move to South Korea.

“Have you made a final decision?” asked the funeral director.

“We think a small church service is best,” I said. “No cremation. You mentioned a part of the cemetery that’s set-aside for Medicaid patients. We’d like you to bury her there. It should help defray the costs a bit more.”

The funeral director told us he’d call the hospital and claim the body from the morgue, and he instructed us to register and pay for the burial plot. After asking us a series of questions for the death certificate and the obituary, my brother and I finally headed home.

During the train ride back to Boston, I listened to the voicemail from Jinny asking me to confirm my availability for the Skype interview the following evening. There was still time to back out. My mother was dead and there wasn’t really a reason to flee anymore. I should’ve stayed behind and grieved with my brother, but I wasn’t thinking about him. I was thinking about myself. When I returned to my apartment, I called Jinny and confirmed I’d be ready for the call.

***

When I was a child, I lived on a street called Pleasant Valley Drive. The name made you think that happy things happened there, but the frequency of blissful moments largely depended on my mother’s mood.

On good days, my mother and I played card games and bingo and sang together while we worked on large jigsaw puzzles at the kitchen table. On bad days, she was prone to flying into fits of rage without any warning or explanation other than the fact that my brother and I were breathing and taking up space.

She became a walking, talking hand grenade, and we never knew exactly when she was going to go off. We constantly hid from her and her black leather belt. When I became the sole target of her rage, I hid underneath the bed we shared. Sometimes I hid in any closet I could find or I locked myself in the bathroom until she convinced me it was safe to come out even though it never was.

Would I encounter the mother who took the time to write condolence letters to the families of the astronauts who died in the Space Shuttle Challenger explosion, or would I face the wrath of the mother who beat me senseless simply because I accidentally spilled milk on the kitchen floor? This was my daily childhood guessing game.

“Don’t make me call the police,” my mother warned as I flailed and thrashed in her arms.

“They’ll come and get you and take you away. Is that what you want?”

My ongoing explosive tantrums became frequent and volatile enough for someone in the neighborhood to finally complain and call child protective services. An exorcist was unavailable, so they sent over a blonde social worker in her mid-thirties who tried to bond with me by taking me to Dunkin’ Donuts and filling me up with crullers and Boston creams.

When she wasn’t showing me how to do stuff like properly answer the door to strangers in case I were ever home alone, she was asking me a string of questions that seemed to go on forever to uncover the source of my tantrums.

I didn’t dare tell her that the source of my tantrums was sitting next to me listening to her questions. I didn’t tell her about the beatings, and I didn’t have the words to describe how they made me feel like I was being split into two people—the girl who was quiet and polite, and the girl who was filled with rage.

Despite my mother’s short stature, she had a commanding presence that filled an entire room. Her infectious southern charm made everyone take notice and gravitate toward her. It was as if they were on a quest to unravel a mysterious code, so they could become part of her orbit. It was no surprise that the social worker couldn’t see past it enough to notice my fear and apprehension.

Eventually the social worker stopped coming to the apartment because she thought I had learned how to tame my anger, but all I did was cover it up and push it down like a clown in a jack-in-the-box.

***

The days that followed my mother’s funeral were as mentally and emotionally draining as the ones that led up to it. My brother and I only had one week to remove our mother’s belongings from her subsidized one-bedroom apartment. The first time I went through her things alone was both daunting and cathartic.

I picked up the crocheted blanket that hung over the back of the recliner and held it tightly against my chest as if my mother were wrapped inside. Her scent of lotion and baby oil was still there, and I breathed it in until my lungs couldn’t take in any more air. I decided that the blanket was one of the few things I would take back to Boston with me.

The countertops were scattered with plastic grocery bags, discarded food wrappers, used napkins, and outdated takeout menus. I opened the refrigerator and found a few bottles of water and Table Talk pie tins. The freezer, which was just as empty, had a couple of leftover ice cream sundae containers from McDonald’s that my mother had been saving next to a bag of frozen spinach.

I touched the various magnets with religious sayings plastered on the front of the refrigerator. They were intermingled with coupons from various pizza joints. I gently removed the linen wreath of plastic flowers I’d constructed in Sunday school when I was seven and given to her on Mother’s Day. I was still waiting for someone to create the perfect greeting card for the mother you love from a distance.

It’s taboo to dislike your mother. In the eyes of society, mothers are the backbone of the family—selfless, loving protectors, and nurturers who are also the teachers of life’s values. In a healthy mother-child relationship, a mother’s love is unconditional. I’ve often wondered if this unconditional love is reciprocal. Is there a price tag on the love we receive from our mothers, and if so, how much are we obligated to pay?

When my mother died, I realized that part of my love had always been obligatory. I felt indebted to her because she carried me for nine months and she fulfilled my temporal needs. In the height of my grief, I mourned the lost opportunity to become close friends instead of enemies. It took months for me to gradually begin to let go of the anger that had always consumed me.

I’d spent most of my life walking on eggshells around my mother, trying not to say or do the wrong thing, but eventually I understood that the stern, domineering woman who ruled my life with an iron fist had a past of her own filled with struggles and difficulties, as well as failed hopes and dreams. Over time I learned that loving and disliking my mother weren’t mutually exclusive feelings, the same way I recognized that she was more than one thing. She was full of imperfect parts just like me.